David Skidmore, Professor of Political Science, Drake University

Michael Moore called it: this election was a referendum on neo-liberal trade policies, which were rejected by working class voters in the industrial Midwest. In his pre-election film “Michael Moore in Trumpland,” set in Wilmington, Ohio, Moore adopts the voice and perspective of a typical white male worker to explain their anger and why Trump’s message hit home with this group. Although he later castigates Donald Trump as a charlatan who offers no answers to the problems of the white working class while praising Hillary Clinton, Moore’s extended recitation of white working class grievances was so convincingly rendered that some interpreted it (erroneously) as an endorsement of Trump.

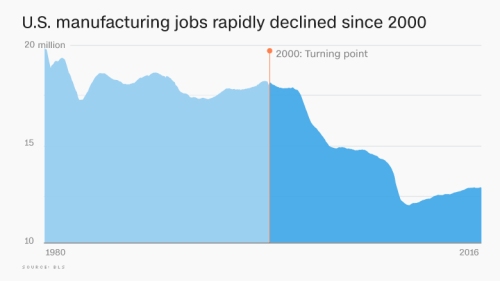

In an election decided by razor-thin margins in a handful of swing states, any number of factors could be cited as crucial to the outcome. Yet as Moore anticipated, international trade policy must certainly rank at or near the top of the list. While some manufacturing jobs have returned to the U.S. in recent years, overall manufacturing job losses since 2000 have totaled around 5 million. The outsourcing of jobs to China since that country gained World Trade Organization membership in 2001 accounts for roughly half of this total. On top of the effects of international outsourcing and import competition, productivity gains since the mid-seventies have benefited capital and top executives rather than workers. As a result of these painful economic realities, white males with only a high school diploma have experienced a 20% drop in real income on average over the past quarter century.

The institutions that white male workers in the past relied upon to serve their interests have shrunken or turned their attention elsewhere. Private sector unions are a shadow of their former selves. The Democratic Party, traditionally allied with blue collar workers, has become dominated by higher income, white collar professionals and corporate interests tied to Wall St. and high tech sectors.

The sense of abandonment by the Democratic Party grew in the nineties during Bill Clinton’s presidency. Having run for office in 1992 as a critic of NAFTA, Clinton turned around and pushed that agreement through Congress after attaching some weak side agreements as a sop to labor. He then negotiated, signed and guided the World Trade Organization treaty through Congress. The next Democratic President behaved in a similar manner, as Barack Obama concluded negotiations on the TransPacific Partnership (TPP) agreement – one chockfull of goodies for corporate interests – and sought a similar deal with the European Union.

These deals – past and future – were especially threatening to blue collar workers of the industrial Midwest who had built middle class lifestyles around well paying factory jobs. Still, the Democratic Party could take the electoral support of these workers for granted as long as the Republican Party remained even more enamored of free trade agreements.

Donald Trump, however, turned Republican orthodoxy on its ears by calling for the rejection of TPP, threatening to raise tariffs on Chinese goods and denouncing corporate outsourcing. Trump’s rejection of the neo-liberal, free trade dogma of corporate elites and their Washington friends won him decisive support among the white working class voters of the Midwest.

Meanwhile, Hillary Clinton’s own criticisms of TPP proved unconvincing. As mentioned, her own husband had, as president, shifted to support NAFTA after running against it and Clinton herself praised TPP as it was being negotiated during her stint as Secretary of State. In any case, no Democratic presidential candidate could credibly present themselves as a critic of liberal trade deals while a Democratic president continued to seek Congressional passage of the same.

The evidence for this interpretation of Trump’s victory is strong. Exit polls revealed that whites without a college degree swung strongly in the Republican direction in the 2016 presidential vote as compared with the three previous elections. The same was true of all voters with incomes below $30,000 (though the swing was still not enough to give Trump a majority among the latter group). Trump won around half the votes of union households, a much better showing than previous Republican presidential candidates.

In 2016 as compared with the 2012 election, five states flipped from the Democratic column to the Republican column. Four of those states – Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin and Iowa – belong to the industrial Midwest (the remaining state to flip was Florida). As of this writing, Michigan appears likely to join the same list, though absentee ballots could change that result. Majorities in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan voted for Democratic presidential candidates in each of the five elections from 1996 through 2012. Iowa voted blue in four of these five elections while Ohio sided with Democratic candidates in three of these five elections.

What changed in 2016? The most obvious factor was a Republican candidate running on an unabashedly protectionist platform combined with a Democratic candidate whose criticisms of free trade policies were unconvincing, to say the least.

Clinton’s troubles were foreshadowed during the primaries when Bernie Sanders, a lifetime critic of trade deals, won a majority of pledged delegates in the upper Midwest states of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Indian, Illinois, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Exit polls taken on November 8 confirm the centrality of trade to many voters. Those who believed that international trade created more jobs in the United States, Clinton was favored over Trump by a margin of 59% to 35%. Those who thought that trade cost jobs, on the other hand, favored Trump by 65% to 31% for Clinton.

Note that in those states that flipped, the Democratic majorities prior to 2016 were never large and Trump’s margins of victory were small. So any significant shift in the white working class male vote that can be attributed to trade policy might have made a decisive difference at the margin.

Trade, as economists love to remind us, produces net benefits to the society as a whole even as the costs are concentrated with those who lose jobs or businesses to imports. In theory, the winners from trade could compensate the losers to ensure greater fairness and to buy off potential opposition to freer trade. In practice, the winners seldom feel a need or desire to share their gains and so the losers from trade and the communities in which they live have little choice but to make do with a few miserably inadequate and ineffective job retraining programs.

Of course, trade is not responsible for the entirety of the problems facing the white working class. Inequality has grown and social mobility has declined for other reasons as well, including technological change and demographic shifts. The devastating effects of the 2008 financial crisis linger, with housing prices still depressed in many parts of the rustbelt. In the minds of working class voters, trade serves as a proxy for the myriad of social, political and economic changes that have hollowed out the middle class in much of the former industrial heartland.

Protectionism is not a real solution for the groups that swung this election to Donald Trump. Neither are policies that encourage more corporate outsourcing. More effective would be investments in human capital (skill-based education) and infrastructure that could attract investment to those regions that have borne the brunt of negative economic trends over the past quarter century.

Still, from a political standpoint, the Democratic Party can no longer afford to ignore the white working class, despite the latter’s declining demographic weight. When Obama pursued corporate-friendly trade deals abroad against the objections of the Democratic Party’s traditional labor allies, he effectively placed a heavy anchor around Hillary Clinton’s candidacy and handed Donald Trump a winning issue. As the Democrats go about recovering and rebuilding from an historic and gut-wrenching loss, a rethinking of how to deal with the distributional effects of globalization and economic change must take center stage.